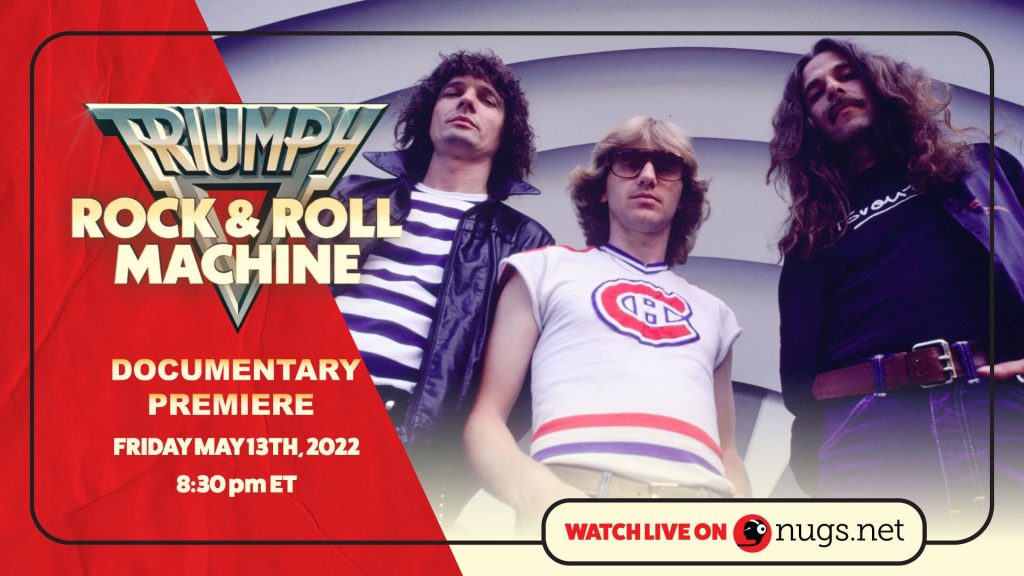

Perhaps no band personified the idea of anthemic rock more than Triumph. The band released 10 records filled with songs about fighting the good fight, following your heart, and yes, the magic power of music. When the music ended, however, the band seemed to disappear. On May 13 their story will be told as the documentary Rock & Roll Machine premiers on nugs.net. Founding member, drummer, vocalist, and writer Gil Moore sat with me to discuss the career of this unique band.

Please press the PLAY icon for the MisplacedStraws Conversation with Gil Moore –

On coming up with the name Triumph – Well, amazingly, there was a young lady in Toronto that was booking my band, and mid-conversation for no reason, other than Mike (Levine) and I were searching for a name, I just said, “Hey, I’m gonna change the name of my band. I’m making this new band, it’s gonna be blah, blah, blah. Got any names? Throw me a name”. And she just went, “Triumph” and one other, I forget what the one other was. I said, “Triumph, that’s awesome”. So hung up from her a little later called Mike Levine and went, “What do you think, Triumph?” He goes, “Done deal”. I lost track of her. I don’t know what her name is even at this point, but yeah, she’s out there somewhere, she should contact Metalworks and I could thank her for the name. :53

On what led to the documentary and why it took so long to be seen outside of Canada – Well, I just woke up one morning, I don’t know what got into me, and I just thought, “Oh, gee. We should do a documentary”. I spoke to D0n Allen our long-time video director, and he went, “Yeah, yeah, we gotta do this”. He then in turn talked to Peter Goddard, who’s a dear friend of the band, a great journalist, actually just passed away a very short time ago, unfortunately, but he approached Peter to write it, Peter started up and he wrote up a treatment and that got the ball rolling. A little later, Don decided his company, Revolver Films, made a co-production deal with Banger and that’s where Banger came in and Banger really handled it from there on out. I just felt we had a crazy amount of footage that most bands don’t have, and so I thought, “Well if was ever a band that had a million hours of video, it was Triumph”. Our archives are all stored at the University of Toronto where we donated them to the music archive, and they have these storage facilities that are phenomenal, they have all the machines, old machines to convert footage to new formats, and things like that. So U of T played a big role, and now it’s nice to see it coming out in America. To your second question here, why did it take so long? I don’t know, it seems like in Covid everything takes long. Ordering underwear from Amazon takes long. I think a combination of factors really, and it’s almost like Canada jumped on it because Bell Media was one of the broadcast partners that had signed on to the deal originally, so they had these preemptive rights to move quickly. We would have preferred to really I think to delay it a bit longer and try to make it synchronous with the rest of the world, but anyway, we’re catching up. 2:05

On if they were surprised that Texas was their big break in America – Not really know because Texas had embraced Rush a short time earlier and another band from Toronto, there was a great band called Moxy, that one of the guys from my terrible-named band Sherman and Peabody, Buzz Sherman, by the way, Rik Emmett had the worst name of all, which is General Mudd, but we won’t get into that. I teased him mercilessly for many years, “You have the worst name ever so don’t talk to me about my names”. But Moxy and Rush were on the radio in Texas and our music, not all that similar, but we’re three-piece hard rock. The same radio station in San Antonio that had picked up on Moxy and Rush, I think they felt there was something happening in Toronto, almost like a Toronto sound, and I think they gave us a look because of Rush and Moxy. That spread very quickly in Texas, we went into Corpus Christi. We went into Austin. Dallas and Houston took a little longer just because they’re bigger markets and bigger radio stations, but of course, when Houston and Dallas take off as they did, then it becomes huge. We end up playing the Texas World Music Festival in the Astrodome and at the Cotton Bowl in Dallas as well. So Texas is a great, great rock and roll market, and I love the Texas people. The other areas in the United States, you have got a remember pre-internet, they had a lot of regional break-outs. So we had, for example, Louisville, Kentucky, who knows why, but right at the same time that we started to roll in Texas, Louisville, Kentucky got behind the band, and Indianapolis, which is not all that far away. But you know when you get your Chicago and Detroit and your Cleveland’s rolling, and then you get into the two costs and you get your LA and your New York, and next thing you know now you’re starting to sweep the country. So it started in pockets, I guess is what I would say. Just because there was no streaming and all the media was regional radio, so if your record was a stiff no one was gonna hear who you are, or until your record wasn’t a stiff there, but you could have a number one record 150 miles down the road. 5:13

On if they felt their studio output began to match their live show by Allied Forces – That’s interesting. I remember a turning point once we were in Fresno, California of all places, and I was doing a radio interview, and it was around the Just A Game era, and the on-air jock said to me, “How does it feel when, as opposed to you trying to get your music on radio, you’re now the sound of radio?” I thought it was a great compliment, and as she said, there was a lot of airplay that album got. “Hold On”, actually, and “Lay It On The Line”, both actually hit top 40 charts as well, which was not our domain. We were definitely an album, AOR, hard rock stations, that was who was playing triumph, but we picked up some of this other airplay as well. That kind of spread the word, I guess, a little farther into different regions. 8:16

On the positive themes of their lyrics – It just came out of us. Another funny anecdote, I remember we were playing in one of the tertiary markets around Chicago, I think was Champaign, Illinois or maybe Peoria, and we had a fan that approached our a crew and wanted to come backstage, and he was really unusual story, and our TM came and said that, “I know it’s before the show, this one person, you gotta let them backstage”, and this gal came back and she had Bibles inscribed with our names, and she gave us, what I thought was a really great compliment, she said “There was too much negativity, there’s too many lyrics that are pushing young people in the wrong direction, and you guys have some very inspirational lyrics.” She was obviously quite involved with her religion at the time, but it was a great compliment. Honestly, Jeff, I think it’s just those are lyrics that just seemed to make sense to us at the time, but when you look back at it, it seems like it was thematic and it carried. Not that all our lyrics were positive, we had other lyrics are girl/boy lyrics and hot car lyrics, and lots of stuff, but there is a sort of a thread that runs through all our music. I would credit Rik primarily with those lyrics rather than myself, but if nothing else, I certainly encourage them, because when he wrote those kinds of lyrics, I thought they were among the best lyrics that he wrote. It kind of pushed me to try to go, “Huh, I wonder if I could write some lyrics that are thoughtful in that regard, and still make a song make sense and hold water with all the guitar tracks and the drum tracks and all that thing”. Something like “Fight The Good Fight”, for example, I know we worked on that. We collaborated on that song, but the lyrical content was Rik and we pushed back pretty hard on some of the lyrics that were proposed, then one day he came in with the hook line, “fight the good fight”, and all of a sudden it was like the whole thing in kind of gelled like this. Looking back at that song, after many years, I go, “Yeah, that really holds water right now”, especially with what’s going on in the world. We’ve always had a big fan base in the military, and I’m sure that won’t abate any time soon. 9:44

On most of the songs being credited to all three members – Well, the three of us did work on every song, but what we realized very, very early on, we were driving to a show, and I made this proposition and Mike was functioning like our record producer. So let’s say on the first record Mike had more influence than Rik or myself because Mike had a lot of experience in the studio and is a very good producer. So he shaped a lot of the songs, so he was kind of on the producer’s stool. Then you had Rik and I both writing sometimes together, sometimes apart, and so there are these royalty things that you have to deal with, with a three-piece band didn’t make sense to me. I just went, “We’re so deep in this together, we’ve committed our lives to this, why don’t we just not really take credit individually because who knows who had the most influence on the song? Was at the great lyric, was that the great guitar part was that the great production, was that the background vocals was it the rhythm? What was it that made the song great?” So it was just one of those “one-for-all” kind of things. We always kinda looked at ourselves as us against the world. When you’re a Canadian band and of course, you wanna make it in the United States, that’s what every Canadian band wanted to do and so few have done. It’s tough to get across the 49th parallel, so we had this three musketeers approach to things, and the songwriting just was part of that, I guess. 12:45

On feeling so strongly about Thunder Seven that they were able to buy out their RCA contract – Well, you know, first of all, nobody can see the future, so even though the amount of money that we spent, it was $3 million bucks to get out of the deal, the way the litigation proceeded and so on. In today’s dollars would be $130 million or something like that. Who knows what it would be? So it seemed like a big tab, so you’re right, we had to have a lot of belief to think that that was gonna be something we can pay back right away, but we did. As far as the record goes, I think at that point, we just believe in our fans, so we knew our fans were gonna support us, and we felt that that record, the Thunder Seven record, was gonna yield some new fans, some new radio play, which it did, the tour was a phenomenal success. No second-guessing anything really that happened there, Jeff, to be honest. The only thing I second guess is we spend some time in LA recording, and I thought we always did better when we were up north in colder weather at Metalworks. It’s too tempting when you’re in LA to goof off. That’s every band’s problem in LA, it’s easier to goof off than go into a recording studio with no sunshine. 15:16

On if the band would have begun to fracture around Sport of Kings even without the record company pressure – Don’t know, it’s a great question. I think it was bound to fracture for different reasons. Like in my case, it was completely different. Most of the story that you hear is about Rik wanting to do solo records and so on, which he did, and that’s true. But the other side of the coin is my father had passed away and I’m the only child, and I had a mother that needed someone to look after her. She looked after me my whole life, I wasn’t gonna leave her alone in Toronto and be in hotel rooms and have her grieving at that time. She needed somebody to look after her. I guess the other thing for me was I was really, really intent on having more children and being there for them. So having roots in Toronto and not living out of a suitcase. The bands that have done it. I don’t fault them for it. I look at what Iron Maiden has done, or what ACDC’s done, and I go, “Oh, those guys were our contemporaries”, and to see them go on and on and on and on, and play year after year for year after year, and I credit them for it. It just wasn’t, you know what I wanted to do. Before Triumph started, I was behind the scenes. I’ve always had an interest in lighting and sound and the theatrics of the big show, so I wanted to get back into that. So Metalworks Studios was something that I had. I love being at Metalworks. I’ve built it up to six studios, and we did all kinds of different artists over the years and got a multitude of gold record awards from other bands from right up until recently, and it’s been a great experience. I wouldn’t change it. So I guess the full answer to the question is, yeah, I think if we kept going one way or the other, the magnet that was pulling me to Toronto was gonna get too strong, the magnet that was pulling Rik towards doing his own records was pretty strong. Mike was in the middle of that, which is not a great place to be. You do reach a stage where when you’ve toured, and America was really, and Canada, America, North America, let’s say, it was our stomping ground. When you’ve achieved what you wanted to achieve, which was for us, the idea that we would be playing the big arenas, be all over the radio. We all have failure bands. Behind every successful band, you have these bands that were just disasters, and we all have them. Mike’s bands were a little bit better than my bands or Rik’s bands. We tease Mike that his bands were better than ours, and we tease Rik that he had a worse name than I did, but none of the bands were really successful. So you get lucky with a band and when you get to that point where you’ve achieved everything we set out to achieve, and then we come back the next year, we do it again with the next record, and we come back and we do it again with the next tour, and then we do with the next tou. And then the next time you’re finished, you go, “Well, okay, now we’ve done it. That’s like a 5-peat, what’s next?” That’s where it kinda slows down, there wasn’t really that inspiration or the aspiration to conquer every other territory on earth. I think part of this is being a three-piece band as well, and we didn’t have the physical stamina. We’d do 90 shows or 100 shows in America to now go and do 20 shows in Germany and then go do eight shows in Japan, and just keep going and going and going and going and going.: Physically, very demanding. And when you’re in a three-piece band and it’s high energy and it’s hard rock, it’s even more demanding. 17:40

On why the band continued after Rik left – I think it was because it was comfortable. We were able to do it on our own terms, which meant we could record the whole thing at Metalworks. We didn’t have a record label breathing down our neck. We just had a record label that gave us a bunch of dough to do it. Unfortunately, the label imploded, it was a big label too, but they imploded right when the record was released, so he has zero promotion. Combination of things, I still like being in the studio, I like writing, had a new co-writer, Mladin Alexander, who I really think is a great writer, Phil, I’ve just always been a Phil X fan, always admired him in other bands, and always wanted to work with him. I’m really blessed because Rik Emmett is obviously a phenomenal guitar player, and Phil X is a phenomenal guitar player, but two different completely different tones, completely different styles. I think Mike and I just had more music that we wanted to get out of our system and we didn’t tour it a lot, and I think we did maybe 10 shows with Phil, so we didn’t really push the accelerator too hard. I think when we did those shows, we realized, “You know what the band that we formed with Phil, even though it was called traumas, we love the band, but it was so different sounding from Triumph”. Phil’s guitars are so much darker and the tone of his voice, of course, and I don’t sound like Rik, so the Rik vocal element, the whole thing. It’s hard to really put into perspective. Other than we wanted to do some more music and we did that record and we loved our time with Phil, but I think we realized at the end of the day, it’s not (Triumph). I think Rik brought it up, “You guys shouldn’t be called Triumph”, so probably we shouldn’t have. It’s difficult in a trio. If you have a five-piece or even a four-piece band of any kind, you’ve seen Van Halen replace members. You’ve seen Deep Purple replace members, you can do it, but to try to replace somebody in a three-piece. Hendrix, ZZ Top, they’ve just had to replace Dusty, which would be, I’m sure very difficult, but trying to replace someone in Rush or trying to replace any of the three-piece bands, much more difficult to change a member out. 22.22

On if Triumph will ever reunite – Well, there’s always a chance. I never, never shut the door on anything in life. Rik, Mike, and I hang out a fair bit, we get together like we’re getting together this Saturday at Metalworks, for example, to record some of the footage that goes along with the Nugs streaming debut. There’s no reason why we couldn’t. But we’re all pretty busy in our own way, our own niches, the things we’re working on. I know I don’t have any bandwidth for any additional projects. I’m super busy with all the stuff I’m doing and kind of fully engaged, so I don’t think so. The shows that we did, the two big festivals, the one in Sweden and the one north of Texas, we did those specifically because we wanted to have the three of us hang together, and it was kind of almost nostalgic thing for us, and we wanna bring our kids out so our kids could participate in the circus for a couple of shows so that they can see how wacky rock bands playing festivals are. It was a lot of fun doing those two shows, but when we think about going back out and doing festivals or something like that, I don’t think so. I don’t think that we have the inclination to do that. Again, it’s part of the inspiration for the documentary, which is back to an earlier question, it’s like this was a way to kind of answer a lot of the questions in the fans had like, “Why did you guys stop?” “You were doing great, Why didn’t you keep going?” So the movie tells the story, it’s just a true story. 25.34

On when he realized Metalworks could be a success for more bands – The very first record that happened was a bit of a fluke. The engineer that we were working with at the time, a guy named Mike Jones, who was a very good engineer, and he also helped design the first room at Metalworks. He said, “When you guys are going out to play, I wanna bring another band in here because I really wanna kinda test the studio out”, I said, “Okay, who is it?” It was a band from Vancouver called Doug and the Slugs. A funny name for a band, but he recorded their debut album at Metalworks and it went Gold right out of the gate. We thought that was a good luck charm, that that record went Gold, and then we had several Tom Cochrane records that all were very successful. They were some of the first records. We were a private studio at that point, and it just kind of if we know you and there’s a reason why, a reason to let you in, we’ll let you in, but it wasn’t a commercial facility per se. 27:46

On Rush – Well, I really admired Rush and so did Mike and Rik, they’re great people. First of all, they’re a great band and they, as I said earlier in the interview, they really helped us by being just, I don’t know whether it was six months or nine months, but it wasn’t much, but they got across the border. That’s the thing. They get picked up in Detroit, Cleveland, and Texas, and they were kind of chumming the pond for us, really, that’s what it amounted to. They’ve been good citizens here in Canada, I can tell you that. God bless Neal Peart. I wish Neal would not have succumbed to that disease, such an amazing, amazing drummer. They’ve all been to Metalworks, recorded there, and they’re just good guys, they’re gentlemen. 29:16